The entrance to the monastery now consists of a group of Mediaeval and modern structures, adapted to present day uses. Some Mediaeval defensive structures have survived, but most of the building was erected between the 17th and 18th centuries to be used for stores and cellars.

Opposite the church are some rooms which have been identified as cellars. They were built between the 17th and 18th centuries together with the stores in the entrance block above. The space is divided into different rooms, covered with a false vault. It uses the mountain rock as a building element.

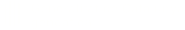

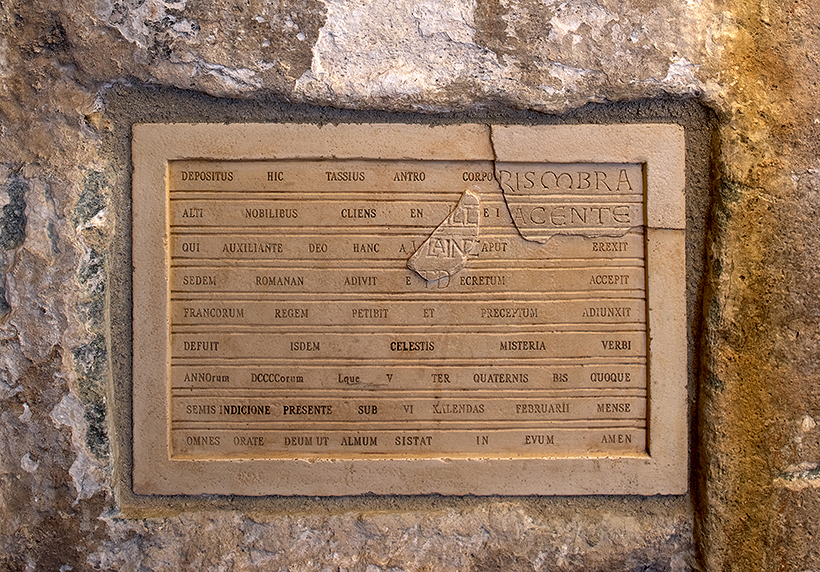

In the 11th century, once the works on the church were finished, the Galilee was built. It is a porch to shelter the faithful and pilgrims. Despite its present appearance, which is due to the looting of the monastery, it was once a monumental space with painted walls, as we can deduce from the scraps of paint that have been conserved.

Sant Pere de Rodes church is the outstanding element of the complex for the originality of some of its architectural elements.

In the early 11th century the buildings that made up the monastery were drawn together with the building of a cloister.

The restoration works have uncovered an old entrance to the monastery located beside the church. A travertine gate led to a corridor excavated out of the rock which ran into the church. With the building of the Galilee, another gate with a basket arch was attached. This entrance, however, was eliminated in the 12th century when the courtyard was refurbished and the present door opened on the centre of the façade.

In all monasteries, the cloister is the starting point around which the other areas are laid out, following a distribution marked by everyday needs. Although time may have changed the function of the buildings, the structure is repeated all around because it is marked by the comings and goings of the monks during the day in fulfilment of the rule.

To the south of the cloister is a room with splayed windows and a ceiling with a pointed vault. According to the building programme of the Benedictine monasteries, this space would have been the communal dining room. It has a lower floor which, judging by its conditions of humidity and temperature, may have been used as a store.

In the Middle Ages the chapterhouse was divided into different spaces. No original element remains to allow us to interpret the use they were put to. According to the layout of Benedictine monasteries this area would have housed the chapterhouse, the sacristy and the area where books and documents were kept. Moreover, above it there would have been the monks’ communal dormitory, located beside the church to make it easier for them to attend the night prayers, especially in winter.

In the monasteries, the porter’s lodge is not a simple entrance point. It marks the separation between the outside world and the cloister. From here only the monks could enter the interior of the precinct.

Situated beside the refectory and connected to the vegetable gardens and the stable area, this room has been identified as a larder. Inside there was a meat cupboard and a cistern.

Inside the precinct is a square from which the entrances to the church and the cloistered space lead off. It was created as part of a rearrangement in the 12th century which extended the monastic complex. To build it the old graveyard was covered to level the ground, which until then had followed the natural slope.

At the end of the Middle Ages, at a time of changes to community life, single rooms were built for the monks on the upper part of the cloister. We can still see the remains of windows, balconies, fireplaces and the old roughcast of the walls, corresponding to eleven dwellings from the 18th century.

Between the 13th and 14th centuries, for the purposes of defence, the tower was built on top of an earlier structure that corresponds to the 10th century façade. The loopholes are the original openings, whilst the semi-circular windows and the doors from the upper cloister are from a later date.

The bell tower was built in the 12th century on the old entrance building, to which the narrow windows at the base of the tower belong.

In the 12th century, above the ambulatory reached from inside the church, a second ambulatory, reserved for the members of the community, was built. Various chapels open off it as well as two arcosolia that conserve vestiges of a 13th century mural painting.

A spiral staircase, which can be seen in the St Michael chapel, led from the church to these chapels on the upper ambulatory. The worship of the archangel Michael gave rise to a kind of elevated chapel or sanctuary, like this one.

Standing out from the monastery complex in the area of the vegetable gardens is a three-storey rectangular building, whose main feature are the porticos. The records show that in the 16th century the ground floor contained the stable. The upper floors were not built until the 18th century, perhaps to lodge the families that worked in the service of the monastery.

To the south-east of the monastery, to take advantage of the sun and the easterly winds that brought the rain while providing shelter from the blustery north wind, is the area set aside for growing vegetables and medicinal plants.

A few metres from the entrance to the monastery precinct are the remains of a building, dating from between the 11th and 12th centuries: the hospice. The emphasis placed on charity and hospitality by the Benedictine rule led to the erection of buildings outside the cloister so that the monasteries could provide lodgings for poor people and pilgrims without their interfering in the life of the community.

Among the alterations made in the 18th century was the building of the new sacristy, attached to the church, with a rectangular ground plan and three storeys.

The abbot, the supreme authority of the monastery, was in charge of the spiritual life of the community, as well as the temporal aspects. To guarantee the proper functioning of the community, the rule laid down a series of posts among which the abbot shared out the responsibilities. In the minutes of a chapter from 1360 the following ones appear: the prior, who also served as almoner, the cellarer (in charge of the administration), the chamberlain (who looked after the monks’ clothes), the piaterius (the tax collector), the sacristan (responsible for all the material elements of worship required), the workman (responsible for the works), the infirmerian (responsible for the sick), the hospitaller (responsible for the pilgrims), the cenator or sopator (who took charge of the monks’ collation on the summer evenings) and the provost (administrating the important possessions).

Near the monastery is the monks’ fountain. Above the spout, which emerges from the head of a fantastic animal, we can read an inscription dated 1588: QUI BIBERIT EX AQUA SITIET ITERUM (whoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again), quoting the gospel according to St John.

The entrance to the monastery now consists of a group of Mediaeval and modern structures, adapted to present day uses. Some Mediaeval defensive structures have survived, but most of the building was erected between the 17th and 18th centuries to be used for stores and cellars.

Opposite the church are some rooms which have been identified as cellars. They were built between the 17th and 18th centuries together with the stores in the entrance block above. The space is divided into different rooms, covered with a false vault. It uses the mountain rock as a building element.

In the 11th century, once the works on the church were finished, the Galilee was built. It is a porch to shelter the faithful and pilgrims. Despite its present appearance, which is due to the looting of the monastery, it was once a monumental space with painted walls, as we can deduce from the scraps of paint that have been conserved.

Moreover, in the 12th century, the Master of Cabestany’s workshop was commissioned to do the sculptural decoration of the church portico. It was one of the first monumental porticos in Catalonia, with the ones at Vic and Ripoll cathedrals.

Because of its location beside the church the Galilee became a privileged burial ground, which housed tombs of noble families with links to the monastery. The area had already been used for burials before the building of the Romanesque church. Remains of anthropomorphic tombs excavated out of the rock have been found.

In the 17th century a great arch was built in front of the Galilee. On top of it was a corbel representing a human bust with long hair.

In the 12th century, under the patronage of the Counts of Empúries, the church portico was sculpted. It was later looted and has now disappeared. All that remains on the original site can be found on the two lower strips of the main door. They are two marble fragments, sculpted with plant motifs, fantastic animals and human heads. The other parts of the portico were scattered and many elements ended up in the hands of collectors.

Nevertheless, some of them have been located and so it has been possible to study it. These fragments show that the work was done with pieces of different sizes both on stone and on reused Roman marble. The outstanding feature of the portico was its abundant figuration, representing passages from the gospels with the typical traits of the Master of Cabestany, such as the expressions and the use of Roman models in the composition.

Among the sepulchres in the Galilee, one has been related to the house of Empúries thanks to a fresco depicting the coat-of-arms of the Counts, with three horizontal red bands on a yellow background.

The house of the Counts was the great promoter of the monastery, which it favoured with generous donations for the purpose of creating a major religious centre within its domains.

Before the refurbishment in the 12th century there was a way from the Galilee to the monastery precinct through a door with a basket arch. Later this entrance was walled up until the restoration uncovered it again.

Sant Pere de Rodes church is the outstanding element of the complex for the originality of some of its architectural elements.

The most recent investigations indicate that the works would have begun in the late 10th century, on top of the remains of a small church, and finished in the second half of the 11th with the completion of the naves and the incorporation of the sculpture.

It is a building with a Latin cross ground plan and three apses built of stones of different sizes, none of them very big, laid in more or less regular courses and, at some points, in herringbone work. However, in the corners and on the pilasters and pillars large, well-carved ashlars were used.

The outstanding feature of the central nave is its great width, whilst the two narrow side naves are corridors that lead to the two-storey ambulatory that runs around the central apse.

The church is the centre of a community life devoted to prayer. The Benedictine rule structures the lives of the monks according to orisons that are distributed over the day. It begins with the singing of lauds, at the crack of dawn, and continues with prime, terce, sext, nones, vespers and compline at the first hour of the night. The night’s rest is interrupted with the celebration of matins; prayers are offered during the night or at sunrise, according to the time of year.

In addition to these community prayers, the monks also practised lectio divina, individual reading and meditation.

The rule also governed the times of manual labour, which is considered an essential part of monastic life. For that purpose St Benedict provided for a distribution of prayers and work adapted to the conditions of each season of the year. According to the ideal of earning one’s bread, the type of work they engaged in varied over time and from one community to another, from farming or craft work to services for the pilgrims or the monastery scriptorium, as is the case at Sant Pere de Rodes.

The originality of Sant Pere de Rodes church lies in the use of a system of superimposed pillars and columns to hold up the central nave, which is 16 metres high.

Another exceptional element is the decoration of the capitals. They have two well marked typologies: the Corinthian with acanthus leaves –a strong Roman influence– and the capitals with intertwining stems that crown the columns of the arches separating the naves.

We can see the contrast between the good conservation of the capitals on the north side, where the church had no windows, and the ones on the south side which, when the sanctuary was abandoned, were left more exposed to the weather and suffered serious deterioration.

A change to the initial project eliminated the columns of the four pillars closest to the entrance. The capitals that were discarded were reused on the walls of the transept and beside the church.

The pilgrims reached the crypt by the stairs on either side of the apse. The semicircular shape of the ground plan enabled them to walk around the repository to venerate the relics, which could not be reached directly.

At one end the base of the altar dedicated to the Virgin of the Cave has been conserved. It seems that the apse that surrounded it was the east end of the original church.

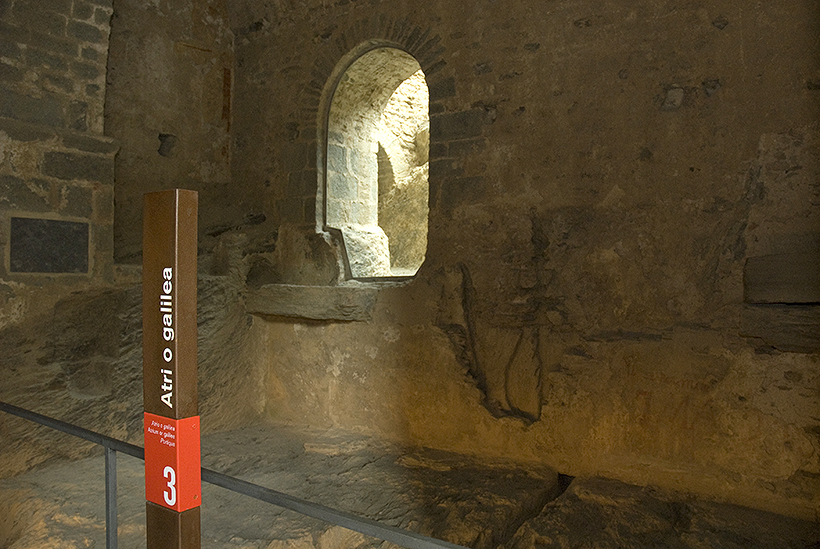

We know some details of Sant Pere de Rodes from the descriptions of the chroniclers. Such is the case of the tombstones of Tassi, promoter of the monastery in the 10th century, and Hildesin, son of Tassi and first abbot of Sant Pere de Rodes, described by Jeroni Pujades in the 17th century. From his writings and the fragments located, it has been possible to reproduce the Tassi tombstone and put it in its original place.

The central apse is surrounded by an ambulatory from which the relics could be worshipped. The pilgrims reached it through the side naves, just wide enough to allow them to walk around the repository where they were kept.

The repository is an underground chamber at the centre of the presbytery where the monks kept the relics, the main attraction for the pilgrims. A 15th century inventory has been conserved listing a large number of relics consisting mostly of parts of the bodies of various saints and martyrs, different elements linked to the passion of Jesus Christ and other objects, notable among them the head and right arm of the apostle St Peter.

In the early 11th century the buildings that made up the monastery were drawn together with the building of a cloister.

This cloister is an outstanding element because few others from the same period have been conserved. Its main feature are the basket arches, somewhat out of proportion. Originally the galleries were covered with beams and the walls densely decorated, as we can deduce from the scraps of paint.

It is a building model typical of the late 10th and early 11th centuries which has survived today because it was buried in order to build the 12th century cloister on top of it. Only two galleries remained in use and the cloister was hidden until it was uncovered during the restoration work in the early nineties. Thanks to that, its original appearance was conserved, whilst the rest of the complex was adapted to changing tastes or needs.

The painting depicts a Crucifixion scene according to St John’s gospel. Its style has similarities with the illustrations of the Rodes Bible. Later the central part was retouched, but only fragments of that second version have been conserved.

After it had been hanging for centuries the painting was badly damaged when the cloister was put underground. For that reason it had to be taken off the wall and restored on a new support.

On the southern wall of the cloister, between two arcosolia, is a framed representation of the figure of a lion. It is a painting from the 12th century whose significance is unknown. It could be a simply decorative element or a heraldic symbol linked to an arcosolia with a funerary function.

These steps led up to the western wing of the cloister which, owing to the unevenness of the ground, was higher than the others. When the upper cloister was built this wing disappeared and the functions of the steps were lost.

To the east of the original cloister are the remains of a large rectangular building, made of ashlars that distinguish it from the other constructions of the complex.

It is a building from the Late Antiquity period, dated around the 6th century, which proves that the area had been occupied since Antiquity. We do not know what its function was, because no archaeological studies of it have yet been done.

The restoration works have uncovered an old entrance to the monastery located beside the church. A travertine gate led to a corridor excavated out of the rock which ran into the church. With the building of the Galilee, another gate with a basket arch was attached. This entrance, however, was eliminated in the 12th century when the courtyard was refurbished and the present door opened on the centre of the façade.

Not open to visitors.

The road that led to the church was bounded by a containing wall, which also functioned as a support for sarcophagi and arcosolia.

Before the 11th century this area was already used as a graveyard. Tombs excavated out of the rock have been found, many of them anthropomorphic. In the 12th century they were buried when the ground was levelled to build the square.

In all monasteries, the cloister is the starting point around which the other areas are laid out, following a distribution marked by everyday needs. Although time may have changed the function of the buildings, the structure is repeated all around because it is marked by the comings and goings of the monks during the day in fulfilment of the rule.

But the cloister is not just a simple way between the buildings, where the galleries protect the monks from harsh weather. According to custom, it is also a place for meditating, reading and working.

In the mid 12th century the cloisters were embellished to make them more sumptuous. In the case of Sant Pere de Rodes, the building of the new cloister was part of a general refurbishment of the complex. It was built over the earlier one, which was put partly underground, thereby extending the surface area and changing the level of movement between the buildings.

The main difference, however, lies in the incorporation of the sculptural decoration in the style of the time, with double columns and figured capitals. Unfortunately, the looting of the monastery between the 19th and 20th centuries destroyed all that splendour.

In the middle of the cloister is the rim of a 17th century cistern, built to take advantage of the part of the cloister that had been put underground. It was fed by a system of channels that collected the water from the roofs.

The rim conserves most of the large carved stones used to build it and on the surface we can still see the holes through which the lead that joined the blocks of stone was drawn.

In some places we can see the efforts made to lower the rock in order to level the ground and obtain a larger space to allow the extension of the cloister.

The looting of the cloister in the 19th and much of the 20th century particularly affected the set of Romanesque capitals, many of which ended in the hands of collectors.

Later the archaeological digs have retrieved some elements that remained in the monastery and could have been part of the cloister. Some of those capitals were restored to the cloister during the restoration.

To the south of the cloister is a room with splayed windows and a ceiling with a pointed vault. According to the building programme of the Benedictine monasteries, this space would have been the communal dining room. It has a lower floor which, judging by its conditions of humidity and temperature, may have been used as a store.

For the monks the meals had a ritual aspect marked by the rule which describes the way in which they must be held. The monks eat in silence listening to a reading by one of them. Both the reading and the obligation to serve at table are weekly tasks which the whole community performs in rotation.

The rule also marks precepts for the meals, regulating the times and amounts, the fasts and abstinences, bearing in mind the needs of the sick, the old and children.

A door, now bricked up, led to the vegetable gardens.

From the refectory a staircase led to the lower floor, on the same level as the first cloister.

On the wall of the refectory we can still see the remains of channels that carried the rainwater.

In the Middle Ages the chapterhouse was divided into different spaces. No original element remains to allow us to interpret the use they were put to. According to the layout of Benedictine monasteries this area would have housed the chapterhouse, the sacristy and the area where books and documents were kept. Moreover, above it there would have been the monks’ communal dormitory, located beside the church to make it easier for them to attend the night prayers, especially in winter.

The chapterhouse is one of the emblematic spaces of the monasteries, where the whole community gathered. It is given that name because chapters of the rule were read there regularly with commentaries by the abbot as a reflection of the guidelines that governed their lives. Here the tasks were shared out and subjects that affected the monastery discussed, since the rule laid down that the abbot had to listen to all opinions before taking a decision.

In the monasteries, the porter’s lodge is not a simple entrance point. It marks the separation between the outside world and the cloister. From here only the monks could enter the interior of the precinct.

The building dates from the 12th century and is part of a total refurbishment of the whole complex, which called for a new porter’s lodge on the same level as the square and the cloister.

Situated beside the refectory and connected to the vegetable gardens and the stable area, this room has been identified as a larder. Inside there was a meat cupboard and a cistern.

The meat cupboard is an underground space with four niches, cavities opened in the wall which were probably used for storage. In the centre, a cistern collected water.

Inside the precinct is a square from which the entrances to the church and the cloistered space lead off. It was created as part of a rearrangement in the 12th century which extended the monastic complex. To build it the old graveyard was covered to level the ground, which until then had followed the natural slope.

At the end of the Middle Ages, at a time of changes to community life, single rooms were built for the monks on the upper part of the cloister. We can still see the remains of windows, balconies, fireplaces and the old roughcast of the walls, corresponding to eleven dwellings from the 18th century.

Between the 13th and 14th centuries, for the purposes of defence, the tower was built on top of an earlier structure that corresponds to the 10th century façade. The loopholes are the original openings, whilst the semi-circular windows and the doors from the upper cloister are from a later date.

The tower is divided into different storeys connected by trap doors. On the upper part a door has been conserved; it led to the machicolation, a protruding balcony with openings for attacking the base of the tower. Of that all that remains is the stones around the tower on which the platform rested.

The bell tower was built in the 12th century on the old entrance building, to which the narrow windows at the base of the tower belong.

It is a structure with a square ground plan and three storeys. On the first two the semicircular windows have no decorative elements, but on the third there are Lombard style elements such as the biforate windows divided by columns, the crowning of blind arches with serrated edges and three bulls-eye windows at the very top of the tower.

In the 12th century, above the ambulatory reached from inside the church, a second ambulatory, reserved for the members of the community, was built. Various chapels open off it as well as two arcosolia that conserve vestiges of a 13th century mural painting.

A spiral staircase, which can be seen in the St Michael chapel, led from the church to these chapels on the upper ambulatory. The worship of the archangel Michael gave rise to a kind of elevated chapel or sanctuary, like this one.

The circular room may have been used as a sacristy. There is no evidence of any chapel dedicated to St Martin; the name comes from a mural painting depicting the saint giving half his cloak to a poor man.

The nave of the St Michael chapel is roofed with a barrel vault, whilst the small apse has a groin vault where we can see a cross made of stone that still conserves the grooves for hanging the lanterns.

Standing out from the monastery complex in the area of the vegetable gardens is a three-storey rectangular building, whose main feature are the porticos. The records show that in the 16th century the ground floor contained the stable. The upper floors were not built until the 18th century, perhaps to lodge the families that worked in the service of the monastery.

To the south-east of the monastery, to take advantage of the sun and the easterly winds that brought the rain while providing shelter from the blustery north wind, is the area set aside for growing vegetables and medicinal plants.

To overcome the slope, two large terraces covered with soil and supported by walls and buttresses were constructed to form the esplanade of the vegetable gardens.

In this sector a water channelling system has been conserved. A ditch built of dry stone collected the water from the mountain and carried it to the cistern excavated out of the rock. From there it fed the vegetable gardens tank.

A few metres from the entrance to the monastery precinct are the remains of a building, dating from between the 11th and 12th centuries: the hospice. The emphasis placed on charity and hospitality by the Benedictine rule led to the erection of buildings outside the cloister so that the monasteries could provide lodgings for poor people and pilgrims without their interfering in the life of the community.

At Sant Pere de Rodes, which was a centre of pilgrimage, the busiest time came with the celebration of Holy Year whenever the Day of the Holy Cross fell on a Friday, a day when the pilgrims could obtain important indulgences.

The service was administered by a monk, called a hospitaller. This post was filled at Sant Pere de Rodes at least from 1221, when the first reference was made, until the monastery was abandoned.

Among the alterations made in the 18th century was the building of the new sacristy, attached to the church, with a rectangular ground plan and three storeys.

It suffered serious decay and all that remains of the original is the façade. It has been adapted as a services building.

The abbot, the supreme authority of the monastery, was in charge of the spiritual life of the community, as well as the temporal aspects. To guarantee the proper functioning of the community, the rule laid down a series of posts among which the abbot shared out the responsibilities. In the minutes of a chapter from 1360 the following ones appear: the prior, who also served as almoner, the cellarer (in charge of the administration), the chamberlain (who looked after the monks’ clothes), the piaterius (the tax collector), the sacristan (responsible for all the material elements of worship required), the workman (responsible for the works), the infirmerian (responsible for the sick), the hospitaller (responsible for the pilgrims), the cenator or sopator (who took charge of the monks’ collation on the summer evenings) and the provost (administrating the important possessions).

In the first half of the 15th century work began on the building of a house for the abbot. According to an inventory from 1633, it was divided into three rooms, a study, the hall and the cellar, although in the 18th century it was converted to redivide the spaces and replace the beams with a barrel vault.

As it was seriously damaged when the monastery was abandoned, the tasks of consolidation of the house were performed later than on other parts of the monastery. In the late sixties only the outer and some of the inner walls were conserved. The work done in the nineties adapted it to the needs of a services building. That is why all that remains of the original building are the outer walls, crowned by battlements, and a biforate window on the main façade.

Near the monastery is the monks’ fountain. Above the spout, which emerges from the head of a fantastic animal, we can read an inscription dated 1588: QUI BIBERIT EX AQUA SITIET ITERUM (whoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again), quoting the gospel according to St John.

The town of Santa Creu, with its church, is part of the Serra de Rodes monumental complex, with Sant Pere Monastery and Sant Salvador Castle. The three elements are closely linked.

The church, which is older than the town, was a possession of the monastery, often disputed by the Counts of Empúries. Before houses began to sprincg up around it, the church already housed the graveyard for the people who lived in the surroundings.

In the early 12th century it became a parish church and the focal point of a town that soon spread under the dependence of the monastery. The inhabitants benefited from its proximity, since it provided them with a certain level of wealth and an economic activity that was largely devoted to its service. When the town reached its moment of splendour between the 13th and 14th centuries, it is calculated that about two hundred and fifty people lived there and, from the materials that have come to light in the excavations, it seems that some had a certain purchasing power.

The town began to go into decline from the second half of the 14th century. The reasons put forward for the fall in popularion include attacks by pirates, the effects of the plague epidemics and the decline of the monastic community itself. The uprising of the serfs against their feudal lords and the Catalan Civil War in the second half of the 15th century dealt the final blow to the town and it was totally abandoned. The church, on the other hand, remained active as a chapel until the end of the 19th century.

Sant Salvador Castle stands on the very summit of Verdera Mountain at an altitude of around 670 m. From the top of the mountain, you can see the Shrine of Sant Onofre at the foot of the cliff on which the castle perches. Beyond to the west, is L'Empordà, which stretches out northwards as far as the Pyrenees, where you can make out the profile of Canigó. The Fulf of Roses and teh Medes Islands are also clearly visible, as is El Montgrí massif, Les Guilleries and El Montseny. To the east, you can see the Monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes and the coast of Cap de Creus, which links to the north with the Gulf of Lion. This commanding position and outstanding view made the castle strategically very important. In addition, the steep and almost inaccessible terrain provided a system of defence that made the castle impregnable.

The castle is mentioned in numerous documents due to the constant disputes between the Monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes and the counts of Empúries, wo vied with each other to control it. The first reference dates from 904, suggesting that the castle was already in existence in the 9th century. Nevertheless, many of the surviving structures date from the 13th century, the time when Count Ponç IV of Empúries ordered that a new fort be built given the poor state of repair of the existing cstle.

With the passing of the years, the strategic importance of castles perched on rocks -the invincibility of which was due to the difficult terrain on which they were sited- declined as a result of developments in weaponry and warfare techniques. Even so, Sant Salvador Castle was still in use in the 16 th century as a look-out post to combat piracy.

The Benedictine monastery of Sant Pere de Rodes is the centre of the monumental complex on the Verdera sierra. The oldest records, dating from the 9th century, make mention of a monastic cell, dependent on the monastery of Sant Esteve de Banyoles, although there are archeological remains that bear witness to an earlier occupation.

The foundation of the independent monastery in the 10th century ushered in a period of splendour promoted by the nobility of the Empordà. Now the centre of feudal and economic power, the community launched a building project that would reflect its strenght. The works went on into the 10th and 11th centuries and essentially included the enclosed area made up of the church, the cloisters and the premises around them.

One of the peculiar features of Sant Pere de Rodes is the existence of two cloisters which were never in use at the same time. The restoration has recovered the original one, which was buried in order to build the 12th century one on top of it. In thsi way we have been able to conserve a building model which has been lost in most cases owing to later refurbishments.

From the 15th century the surrounding countryside was ravaged by constant looting, pirate raids and wars which more than once forced the monks to abandon the monastery.

The economic revival of the 18th century provided the means to undertake new projects, such as the refurbishment of the precinct around the cloister, consisting of service buildings, mostly erected in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the planned works were never carried out because in 1798 the community abandoned the monastery definitively. From that time the complex went into a swift decline.

accessibility | legal notice and privacy policy | cookies | © Departament de Cultura 2018 Agència Catalana del Patrimoni Cultural